Elizabeth Martha Anne Browne (but known as Pattie) was born at Camp Hill, Tullamarine Victoria on 1 January 1863. She was the third of the eleven children of Hugh Junor Browne and his wife Elizabeth (née Turner). She later married Alfred Deakin, sometime Premier of Victoria, and Prime Minister of Australia.

Throughout her married life, Pattie devoted herself to her

family and charity work, especially in the area of child welfare. She encouraged her three daughters to live a

life of service to others.

For a listing of her philanthropic work, see the Australian

Women's Register.

Vera

Deakin and the Red Cross, by Carole Woods, was published by the Royal

Historical Society of Victoria in 2020.

While reading this book I was interested in the reference to the Anzac

Buffet, and most particularly just exactly where it was in St Kilda Road. It required a little bit of digging, but now

I know.

When the war began in 1914, the Australian Army put its

efforts into equipping and training their recruits for war, but it was the

women of Australia who threw themselves into providing comforts and morale

boosting for young men separated from their friends and family. Though the troops were surrounded by young

men similar to themselves, they could be

lonely for their wives and girlfriends, mothers and sisters. The women of Australia understood this and

with a will they threw themselves into providing home comforts for the

men.

The women also excelled at seeing a need and working out a

way of filling that need without the support of a huge organisation around

them. The Soldiers’ Refreshment Stall,

later called the Anzac Buffet, is one example of a need met by a group of women

without a formal organisation. Leadership was provided by older women, self-selected

largely through class and status, and the rest generally formed a supportive

group around them with no formal structure required, only a willingness to work

hard and fill a need.

The 5AGH was located in the newly completed Police Hospital.

Before ever having admitted a patient, the Police Hospital was taken over by

the Army to provide for soldiers yet to embark and also by wounded returning

from Gallipoli. The first patients were admitted in March 1915.

A news

article described this drawing: “The Building elevation shown above is that of

the new police hospital which is in course of erection upon a site on the

corner of St Kilda road and Nolan-street, which was formerly part of the old

Immigrants Home property.” (Argus,

20 June 1914).

The hospital faced Nolan Street on the north side, now

renamed Southbank Boulevard. St Kilda

Road passes in the foreground. It

reverted to a Police Hospital in 1920.

The Police Hospital from a drawing of the entire

Police Depot in St Kilda Rd.

See The Heritage-Listed Old Police Hospital is Born Again.

Former Prime Minister Alfred Deakin had accepted an invitation to form a delegation to visit the USA in January 1915, and despite his daughter Vera being anxious to find a way to serve the war effort, she was obliged to accompany her parents to California. Pattie, his wife, and Vera Deakin had been original members of the British Red Cross organising committee in Melbourne in 1914, but left the committee when they travelled overseas with Alfred. Both of the women were accustomed to leadership roles, so on their return they had to find a new activity rather than appropriate their former positions, now occupied by other women. The Australian Red Cross was providing workers in the kitchens at the 5th Australian General Hospital (5AGH), and it might have been their suggestion that there was a need for a refreshment service for the men who had long waits to see doctors and other health professionals.

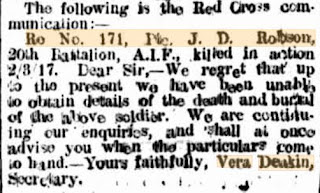

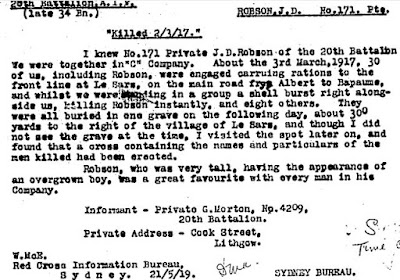

Vera Deakin worked with her mother and Jane McMillan in the

establishment of the Soldiers Refreshment Stall, but on 21 December 1915, Vera

and her friend Winifred Johnston left Melbourne on a ship bound for Cairo, to

begin her important war work with the Australian

Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau.

The Deakins arrived home in early July 1915. On 29 August 1916 The Argus reported

that the first birthday of the Soldiers’ Refreshment Stall had taken place on

the previous day, implying that the Deakin women had taken less than two months

to set up and commence their work in 1915. There were formalities to go through – permission from the authorities at the

5AGH, a tent to work in, some basic equipment to assemble and the first

donations of tea, coffee, cocoa and bread, cake and appropriate provisions for

soup, and a team of volunteers to operate the stall seven days a week. They kept this up for four solid years, with

the work building from 4,000 per week in 1916

to an average of 1,000 “serves” per day in 1919. (The Herald, 11

Nov 1919, p 1).

The Stall served hospital

outpatients, drivers, men from the camps, orderlies and all soldiers who

had a need of it. Ten and later 15

volunteers turned up each day to run the stall. The group photographs show thirty-six

and forty-eight volunteers respectively, and thirty-five are listed

individually in the Voluntary

War Workers Record, Australian Comforts Fund, 1918. Between 400 and 500 volunteers assisted

throughout the period of its operation, and 130 names were on the roll in 1919.

(The Herald, 11 Nov 1919, p 1).

From the Ladies Letter, Punch, 4 May 1916:

“The Base Hospital Soldiers' Refreshment Stall celebrated Anzac Day by entertaining over two hundred overseas "Anzac" men, presenting each guest with packets of cigarettes, sweets, and matches. There was no speechifying or boresome formality about the affair—just a homely, cheery greeting characteristic of this pleasant "corner" run by the "Serve You Right Sisters," as the volunteer- caterers at the S.R.S. are affectionately dubbed by their khaki customers. Each arrival was just enjoined, in greeting to "remember the day, and what it commemorates” and, indeed, the majority, of those present, with limp, hanging, empty sleeves, shaded eyes and pathetic bandages, had every reason to remember.

This "corner," by the way, is kept so busy now that it requires an average "of ten helpers a day. There is no committee, no board, no red tape. Practically every suburb is represented among the helpers, among whom exists a wonderful esprit de corps and absence of friction. Over 900 men per day are fed and "mothered" very often, or a mean average of 4000 per week. Supplies and cheques just flow in without any necessity for canvassing or pleading on the part of the organisers — not in huge, spasmodic lumps and amounts, mind you. There is just that knowledge among the S.R.S. that they know where to turn for support ; a regular fifty pounds of tea, for instance, keeps the caddy replenished from one firm ; so many pounds of cake per week arrive from another ; and so on. A leading Prahran emporium the other day handed in a cheque for £25, saying that was only the beginning of what the employes intended to do as a recognition of the fine work being done.

"By their works ye shall know them," and the gratitude of the soldiers who have been administered to, and of their relatives and friends, is constantly being signified in a variety of ways. One soldier—a baker by trade—sends along his "thank you" every week in the form of a trayful of pastry cook's goodies. The mother of one soldier who was shown kindness by these volunteers tried to express her gratitude by offering little gifts to the chief ministering angel. This was gently declined, with the explanation that other soldiers who were not able to afford such presents might be made to feel unhappy; but if "Mum" liked to send along some scones or something they would be very welcome. Now, with frequent regularity, a package of home-made cakes, scones, etc., arrive at the buffet from this grateful "Mum." In addition to the hundred-and-one little services which the workers in this "corner" are able to do, such as sewing on buttons, writing letters (for those, alas ! incapacitated), interceding with authority, helping through inquiries, comforting relatives, etc., a regular "Returned Soldiers' Aid Fund" has become established.

Temporary loans for small amounts are advanced to those who need them. Poor Billy Khaki is so often "stoney," awaiting pay arrears—goodness knows why and how ! This temporary accommodation is given, with discretion, with common-sense judgment, but without cold official inquiry, without red tape, without even hesitation" as to its being "deserving." And how it is appreciated ! In nine cases out of ten all such advances are returned in due course. And as for the tenth—well, what are we all supposed to be doing, and thinking, and talking of, and bragging about, if it is not helping soldiers in need? Another excellent movement instituted is for the provision of suits of civilian clothes for discharged invalids. A soldier is given one outfit by the Government when he doffs his khaki. If that gets wet or damaged he can very seldom afford to buy another. Husbands and friends of this helpful sisterhood are only too glad to contribute suits for this, purpose, particularly duck and linen, outfits for on board ship for those discharged men who have to return to England”. (Punch, 4 May 1916, p 32.)

The soldiers', new refreshment stall at the base hospital, St. Kilda road, was opened on November 30 by the acting State Commandant, Brigadier-General R. E. Williams. The pavilion was built at the expense of the Defence department in order to provide better accommodation for carrying on the work than the old structure afforded. The new stall has been christened the "Anzac Buffet," and in it returned soldiers are provided with refreshments at a nominal cost. The buffet is conducted by a number of patriotic sympathetic ladies, who give their services, voluntarily. After Brigadier-General Williams had explained the launching of the movement two and a half years ago by women eager to serve their country in any capacity, Mrs Alfred Deakin (directress) responded, thanking the Defence department for the gift of the pavilion, which would greatly assist in the work they were devoted to, at which announcement the soldiers cheered enthusiastically. Luncheon was subsequently served, and amongst those present were Brigadier-General and Mrs Sellheim, Mr. Alfred Deakin, Colonel F. D. Bird, Major and Mrs. Courtney, Colonel G. Cuscaden, Lieut.-Colonel Pleasants, Matron C. Milne, Mr. T Trumble, Mr. F. Gates, and others. (The Australasian, 8 Dec 1917, p 41)

At the same time as the improvement in accommodation and name change for the buffet came also some smart uniforms for the women.

On 1 August 1918 the Punch featured the Anzac Buffet in a page of photographs, by F W Tolra:

SERGEANT WITH 9 CHILDREN PAYS

After four years of useful service the Anzac Buffet

"I am just out of hospital and I have nine kids,

help to me, until I got my settlement. It has

buffet from its inauguration in a bell tent,

in future, continue as a canteen for patients

Senator Russell, Acting Minister for Defence,

front. Mr Groom, Acting Attorney-General,

and he had heard that when the statesman

Mr Herbert Brookes, in responding on behalf

diggers, and, as most of them had relatives

In response to repeated calls, Mrs Deakin

THE little Iron shed on the St. Kilda road, next to

a free mid-day meal to any Digger who cared

(The Herald, 5 Feb 1923, p 6.)

The two women who were most synonymous with the Anzac Buffet in Melbourne, Pattie Deakin and Jane McMillan had, however, bowed out in 1919, thanking the Diggers:

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ARGUS.

Sir, In closing the Anzac Buffet we should like to

JANE McMILLAN

Pattie’s husband Alfred Deakin, former Prime Minister of Australia, had died on 7 October 1919, just a month before this gracious farewell from the two ladies. Jane had lost her only child in September 1917, but somehow had drawn herself together and returned to work at the Anzac Buffet.

Most diggers understood that the women of Australia had their own

burdens to carry – sorrow, grief, anxiety, and often found on their return to

Australia, that their families had been badly affected, with their parents or

grandparents carried off by the constant stress of having their sons away, or

the death of cousins and nephews, or deaths of sons of their close

friends. The war left a shadow on

Australia for many decades.

I need to disclose that I am a member and volunteer of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria.

SOURCES

.jpg)