Wednesday, November 23, 2022

Claiming a Brother

Sunday, October 30, 2022

Private Arthur Jabons Lane, no known grave

The Australian War Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux in the Somme departement in France contains the names of 10,773 men who died but who have no known grave.

Rod Martin tells the story of one of those men. Arthur Lane enlisted in Sydney, but his family lived in Wonalta Terrace, Mt Alexander Rd, Flemington. Arthur's younger brother James Lane was also killed in action in October 1917.

Arthur served with the 54 Infantry Battalion, a Sydney battalion. He probably arrived in France in time to have Christmas Dinner with other reinforcements, and was taken on strength of his battalion on 1 January 1917, then located at Buire in Picardie, just south of the Belgian border.

Arthur was killed in action just 5 months later. Read Rod Martin's account of Arthur's part in the war.

Saturday, July 16, 2022

The Disaster at The Nek

Tpr Robert Kerr, courtesy of Kim Phillips,

An early recruit to the AIF in 1914, Robert Kerr, a commercial traveller of Brewster St, Essendon was assigned to 8 Light Horse Regiment. When the campaign opened at Gallipoli, it was quickly apparent by the terrain and the danger from Turkish bombs that horses could not be used, and they were left behind in Egypt. The Light Horsemen became Infantrymen.

The British generals were keen to break through the stalemate on Gallipoli and created an elaborate plan of feints, diversions and charges in August 1915. The 8 LHR part in the plan involved a bayonet charge at The Nek against Turkish machine guns. Of course it would work!

Rod Martin takes us through the plan, and explains why it didn't work. The stupidity of the British Officer Class might have had a bit to do with that. (My interpretation, but I think Rod would agree.)

Robert Kerr was a part of the charge which was seen to be so stupid that some of the men were said to have left their guns behind, and went bravely to their deaths. Read Rod's story about Trooper Robert Kerr.

Sunday, April 24, 2022

Vera Deakin and the Red Cross

When war broke out in 1914, Vera Deakin, daughter of Alfred Deakin, former Prime Minister of Australia, urgently wanted to do something beyond knitting socks and balaclavas for soldiers, but Australia saw little role beyond that for Australian women in the war. She joined the newly formed British Red Cross (later renamed the Australian Red Cross) in Melbourne, and did a home nursing course, but the VAD auxiliaries then being trained would not leave Australia for some time.

She cabled to Norman Brookes, then one of two Red Cross Commissioners in Egypt, to see if he had something she could do. Norman was the brother of her brother-in-law Herbert Brookes, married to her older sister Ivy. Norman immediately cabled back that she should 'Come at once and bring as many like yourself as you can find'. To the strong objection of her father, Vera booked a passage to Cairo with her friend Winifred Johnston, and thus began a very strong working partnership between Vera and Winifred for the Australian Red Cross.

The Australian Red Cross Society (ARCS) had been working in Egypt with the British Red Cross in running an enquiry service covering the Gallipoli and Egyptian campaigns, but Norman Brookes wanted to form an Australian bureau to concentrate exclusively on Australian wounded and missing soldiers. He wanted Vera and Winifred to undertake the leadership. At the time Lady Barker was in charge of the British Red Cross operation in Cairo, and she helped them to set up their service and trained them to run their Bureau. Vera became the Secretary, and Winifred Assistant Secretary.

Mere weeks later the ARCS intended to replace Vera with a man, but Lady Barker defended the two women vigorously, and Vera was allowed to remain in place. Vera's whole life to this point had prepared her well to undertake a leadership role, and she did it will verve, skill and compassion.

Families back in Australia whose relatives had been reported missing were in anguish about their fate, and wrote letters to the Red Cross and the Army to discover what had happened to them, and if deceased, had they been decently buried. Searchers went out to the hospitals and army bases armed with lists of missing men to see if they could find someone who knew what had become of them. Volunteer staff then compiled the reports and letters were written to families on the results of their searches. Although the British used male and female searchers, the Australian Bureau used exclusively men, as it was felt the men would answer the searchers' questions more openly.

After the evacuation of Gallipoli, the BRCS and ARCS shifted their operation to London, which followed the shift in the Australian troops from Egypt to France and Belgium. The horrendous numbers of wounded and missing troops meant that the ARCS Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau had to put on more volunteers and more searchers to handle the tens of thousands of enquiries per year. Australian names were added to the British searchers lists to try and make their enquiries as widely as possible.

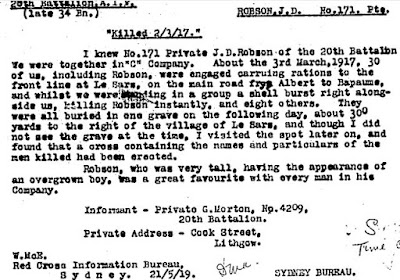

The ARCS made every effort to trace missing soldiers, sometimes taking years to locate a soldier who could report to them what had happened. On 23 March 1917 Private J D Robson was killed in action in France. Vera's response to the family was reported (1917, September 25). The Wingham Chronicle and Manning River Observer.

True to her word, the Bureau kept making enquiries about Robson, and finally in 1919 they located a man who could provide details of his death and burial.

By the date on the above response, it would appear the ARCS had tracked the respondent down to his home in Sydney. This was but one of tens of thousands of enquiries made to the ARCS Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau.

In order to track down as many of the missing as possible, the Bureau began seeking out lists of Prisoners of War coming out of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva, and took it as one of their roles to maintain contact with those prisoners to keep their morale up, and to send them food parcels. One of the airmen with whom the Bureau and Vera herself corresponded was a man whom she would later marry, Captain Thomas Walter White, whose next of kin, his mother, resided in Moonee Ponds.

One of the things that made Vera peculiarly suited to the work on the Prisoner of War records was that she had studied German, in Germany, prior to the war. She was able to understand the reports of prisoners being sent to the ICRS from Germany, and interpret for the volunteers. This was in marked contrast to the non-German speaking Army Officers who were required to send reports to the next of kin in Australia. The Army became greatly exercised by the fact that Vera could get her Wounded and Missing enquiries responses back to Australia before the Army could make their reports, and they wanted her to stop it. Vera was not impressed.

Apart from the massive amount of work going on at the Bureau, Vera and her friends entertained Australian soldiers coming to London on leave, taking them to the theatre, picnics, and sight seeing tours, and entertaining them to tea in their flat. Many of these young men later turned up in casualty lists, to their distress.

At the end of the war, the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiries Bureau prepared their records to be returned to Australia for the Australian War Museum, later part of the Australian War Memorial. These records were digitised a few years ago and can be searched by name at the AWM website.

Captain Thomas White's correspondence can be seen here.

All the remaining Bureau records can be searched here.

Vera was awarded an OBE for her war service with the Australian Red Cross in the Great War, but it was not the end of her work with the Red Cross, nor other community work that she took up after her marriage, such as with the Royal Children's Hospital and other charitable causes. In WW2 Vera and her comrades put their Red Cross uniforms on again, and set to work to deal with further missing and wounded enquiries. Hers was a life of extraordinary service to Australia.

In 2020 the Royal Historical Society of Victoria published Carole Wood's book about Vera Deakin and the Red Cross.

In full disclosure I report that I am a member and volunteer with the Royal Historical Society of Victoria.

Prisoners of the First World War - ICRC Archives

On 21 August 1914, the Central Prisoners of War Agency was created to collect information on prisoners held by the warring parties. Countries holding prisoners of war sent lists of their prisoners’ names – albeit not consistently – to the agency in Geneva. In this way, the agency collected around 400,000 pages of names.

Volunteers in many countries took on the herculean task of receiving, recording and forwarding reports of prisoners of war to enable relatives in far away countries to know what had become of their soldier sons and husbands.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) have digitised their records and made them available to be searched online by individual name. Other resources on the website are postcards of prisoner of war camps, reports from inspectors on prisoner of war camps, and personal accounts of life in prisoner of war camps.

Go to the ICRC website and search for information about a particular prisoner of war. Take time to investigate how the website works to get the most out of it.

Sunday, March 27, 2022

Thirsty Work Crossing the Sinai - Trooper J E Quinlan of Shuter Street

James Quinlan was a 19 year old labourer of 29 Shuter St, Moonee Ponds when he enlisted in January 1916. By June James had arrived in Egypt and was assigned to the 3 Light Horse Machine Gun Squadron. He spent the rest of the war in the Middle East with the Mounted Division under Major-General Harry Chauvel.

Rod Martin carefully traces the course of James Quinlan's war, the task of the mounted division being to drive the Turks out of Sinai then into Palestine, the ultimate goal being Turkish headquarters in Damascus, Syria.

The Middle Eastern campaign was a hard one, with one of the worst hardships being the shortage of water. One 3 Light Horse Brigade man later commented :

I can honestly say that, except on special occasions, I was thirsty for the whole nine months we were crossing the Sinai.

If you had a relative in the Middle Eastern campaign, Rod Martin gives an excellent insight into that campaign with the experiences of James Quinlan and the 3 Light Horse Brigade.